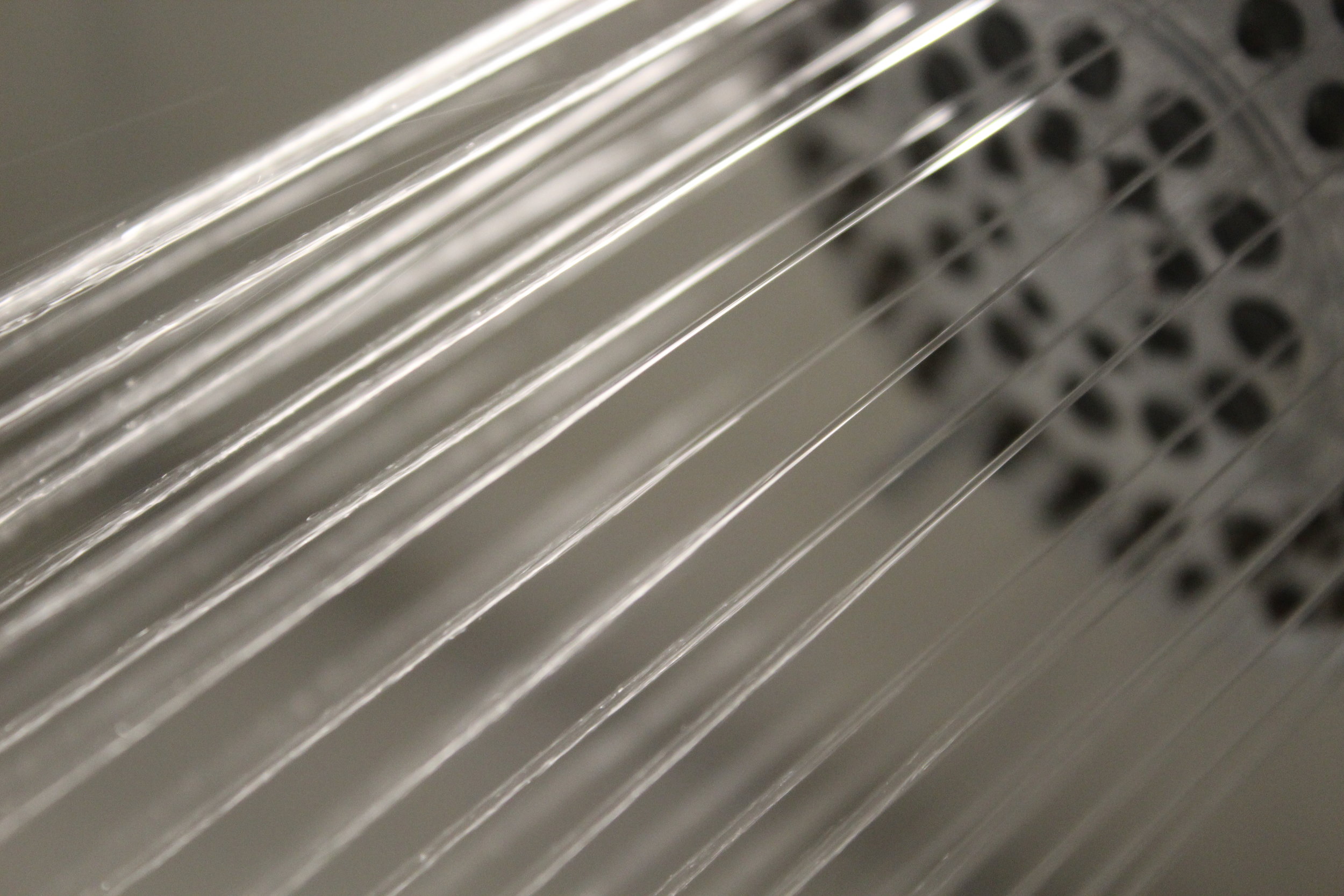

Although I can no longer read the tiny print on, say, a prescription bottle or billboard, I do enjoy examining things close up, especially with the macro lens on my camera. It’s reassuring to discover there are many interesting moments going on where I can’t see them. Right now, the world is thinking a lot about the invisible, but I’m not drawn to the invisible as much as I am the barely visible, the small world on the cusp of my ability to focus.

For some reason, I always decide I want to go take pictures with my macro on windy days. This, of course, is stupid, because the finite depth of field of the macro requires steadiness of subject. Only a sliver of the world will be sharp in these photos, so that sliver has to hold still for a fraction of a second. I find myself in the garden, squinting through my lens, using manual focus to guess at when the object has stopped quivering, or when its quivering has landed it in that sliver where it will be rendered unfuzzy.

The photos themselves aren’t particularly artistic, but to me they offer a glimpse of how things are put together. When I look at a flower or fern with my usual foggy eyes, they are certainly pretty, but when I see the same bud or frond rendered by the gaze of my macro, pulled up on my laptop as a full-screen image, these subjects become something to study in order to figure out what makes them the larger things I generally perceive and how they work.

I don’t know that I would want the superpower of macro-vision. I think I would be paralyzed by the enlightenment of perceiving details that right now I can’t quite see. And though with my camera there’s a short wait between guessing what sliver I’ve caught with my lens and discovering the truth, I appreciate the moments of mystery, wondering what surprising landscape will be revealed in places I thought I’d visited, in what I had assumed I knew.

(See if you can guess which planet you’re on in my photos.)

1: Peony; 2: Oriental poppy; 3: Maidenhair fern; 4: Japanese fern; 5: Tall bearded iris; 6: Amsonia; 7: Prickly pear; 8: Pagoda dogwood; 9: Meadow rue; 10: Norway spruce; 11: Foamflower; 12: Columbine; 13: Rhododendron; 14: Dandelion; 15: Winter aconite; 16: Ginkgo (male); 17: Dwarf crested iris; 18: Cherry blossom; 19: Ostrich fern; 20: Common lilac; 21: Blueberry; 22: Daphne; 23: Asparagus